3 Curiouser and Curiouser

Redirecting Research Anxieties

Christine Elliott and Lauren Movlai

“For students facing research concepts that cause them anxiety, they need practice and a safe space to follow their curiosity in taking broad topics, breaking them down into searchable concepts, and navigating the abundance of resources available through the library. . .”

Introduction

First and second-year students are understandably overwhelmed when starting their research journeys. Academic expectations and the pressures to succeed can increase student anxieties when beginning any research assignment. Where do they start looking for ideas? What do they do when they can’t find anything on their own? By creating spaces where students are encouraged to embrace creativity and to try and fail on a small scale, we can help ease their academic anxiety.

This chapter identifies challenges experienced by students with diverse needs and experiences at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, focusing on first-year courses, including orientation and course specific-instruction sessions for 100-level students. We outline activities that help students embrace creativity and overcome research anxieties and examine how instruction librarians can make research inquiry and exploration less daunting. Each lesson/activity is grounded in the standards outlined in the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy, specifically “research as inquiry” frame. The exercises and activities in this chapter include:

- Using “gamification” to enable students to explore library services at their own pace with a digital escape room

- Creating low-stress activities with applications like Slido

- Providing in-class opportunities for students to work through activities and challenges with peers in small groups

- Using keyword identification tools and collaborative worksheets/activities for narrowing and revising broad topics

- Providing prompts for research “dead-ends”

In addition to highlighting these highly adaptable exercises for a wide range of instructional and outreach needs, the chapter includes survey feedback from students participating in 100-level classes that have a library instruction component during the Fall 2022 semester.

Literature Review

This chapter is greatly tied to the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) frame “research as inquiry” in that the focus is on how curiosity or inquiry-based activities are used to address the ongoing prevalence of library anxiety in first-year college students (ACRL, 2015). Students show ongoing struggles in formulating their own research question early in the research process or identifying the main purpose or question in scholarly publications (Fister, 2022; Scharf & Dera, 2021). Having a clear and focused research question or focus is essential for driving curiosity and inquiry-based exploration of available resources (Badia, 2016; Taylor, 1962; Van Der Meij, 1994). It is important for library interactions during the first year to focus on honing this skill.

While it is established that many, if not most, first-year students struggle with university level research, it can be argued that these challenges are at least in part due to transitioning already present research skills to the research norms of their university (Kocevar-Weidinger et al., 2019). Therefore, when teaching information literacy (IL), instruction should acknowledge and build from these known skills. This is sometimes known as an asset-based, or constructivist, approach to learning (Cooperstein & Kocevar-Weidinger, 2004). One approach to asset-based IL instruction is asking students to list five things they researched in their personal lives during the past year (Kocevar-Weidinger et al., 2019). The responses were coded into five categories, one being reason. Within the category of reason (a motivating factor for information-seeking behavior?), the two biggest factors were curiosity and problem solving. The researchers found that “in addition to curiosity, our participants’ research was frequently motivated by problems that varied greatly in subject, urgency and complexity. Our participants proactively sought answers to their individual problems in a range of areas, including active citizenship, legal matters, health issues, college choices and future careers” (Kocevar-Weidinger et al., 2019, p. 176). These examples show that, while students view their own personal research as inquiry- and curiosity-driven, there is room to infuse the same curiosity into class assignment-driven research.

Another barrier to students further developing their research skills is library anxiety; a well-documented, and well reported, ailment experienced by college students. This is especially present in first-year and first-generation students (Carlile, 2007; Clark, 2017; Hodge, 2022; Jiao & Onwuegbuzie, 1997; Lemire et al., 2021) who are starting their academic careers with little, if any, research and library experience. It can also be helpful to look at how library anxieties contrast in different populations. One study, for example, found that African Nova Scotians expressed very positive attitudes toward public libraries prior to their university experience (Fraser & Bartlett, 2018). Despite these positive attitudes, they experienced an increase in library anxiety through their years attending university. This was due to several barriers, but interactions with library staff were a prominent factor. Caucasian Nova Scotians however, initially had more library anxiety, which then declined slightly during their enrolment. Students felt that librarians/staff “were not visible in the library and were too few to accommodate the needs of students” (Fraser & Bartlett, 2018, p. 12). This fear of the library, and library staff, can result in students refraining from asking for research assistance despite their need for support (Hodge, 2022; Lemire et al., 2021).

Another source of anxiety, for first-year students especially, is the research process itself. Many first-years are just beginning to explore and establish their knowledge of particular subjects and do not have a journal or author/scholar to use as a starting point (Badia, 2016). In many cases, the use of research paper assignments in the first year is to allow students to explore existing literature on a subject. However, instead of interpreting this as an opportunity, many students see this as a test to meet the basic requirements of the assignment while nervously avoiding plagiarism (Fister, 2022)., 2022).

Conversely, there is also a growing focus in the literature about overconfidence in first-year college students (Kruger & Dunning, 1999), which suggests that “persons who are not proficient in a skill tend to overestimate their abilities in that skill and have difficulty recognizing proficiency in others” (Hodge, 2022)–this is called the Dunning-Kruger effect. If a student has trouble with a research task, they will place the blame on the library’s confusing website or building as to why they are unable to succeed as opposed to reflecting on their own skills. Helping students realize that there are research and information-seeking skills that they still need to develop is part of the battle for librarians.

One way to combat library and academic anxiety, as well as this overconfidence phenomenon, is through approaching research with curiosity. Intellectual risk taking, and similar terms such as creative learning, have slightly different definitions depending on who’s doing the defining but most center around the importance of students taking the risk to be wrong, change their assumptions or beliefs with new information, and pursue inquiry (Teagarden et al., 2021). “Creative curricular experiences are designed by allowing for one or more of these elements to be determined by students (e.g., students can come up with their own problems or task, their own process for addressing the problem and their own ways of demonstrating success”) (Beghetto, 2021 p. 607).

It is impossible to engage in the creative process without some failures. Therefore, a willingness to keep going through potential failures and to accept potential failures are both extremely important. Failure can lead to positive outcomes through the iterative process, but it is also a useful approach that leads us to recognizing and accepting the challenges of uncertainty inherent in problem solving and creative thinking (Henriksen et al., 2021). In educational settings, failure assumes a negative context, even while creativity and curiosity are touted. As education moved more towards measurable outcomes and standardization, the acceptance of uncertainty, unpredictability, and failure became less and less. Many educational systems view failure as a problem to be solved rather than accepting it as part of the learning process (Henriksen et al., 2021).

Creative learning requires more risk-taking and therefore a greater chance of setbacks and failures. Adaptive risk-taking is an approach where risk-taking leads to the development of adaptive behaviors and outcomes (Beghetto, 2021). These adaptive behaviors and outcomes are directly linked to having productive and creative curricular experiences. Adaptive risk-taking can lead to emotional reactions regarding setbacks and failures, which educators should be aware of and prepared for (Beghetto, 2021). Establishing an environment where risk taking is expected and encouraged, and where students are supported, is one way to offset this. This kind of environment lends itself well to creative learning opportunities where failure can be reframed as productive failure that leads to a better solution.

UMass Boston

The University of Massachusetts, Boston (UMass Boston) is a higher education institution that provides undergraduate and graduate-level programs to a highly diverse student population. With around 15,600 enrolled students (based on academic year 2021-2022), UMass Boston serves the surrounding community as the only public research university in Boston. Healey Library serves as the campus library and has diverse offerings to meet the research needs of the surrounding community, including first-generation, commuter, international, graduate, undergraduate students, and non-UMass Boston community members. The 2021-2022 academic year included 74 library sessions for first-year students, provided by the Reference, Outreach, and Instruction (ROI) department. Many of the students that attended these sessions were first-generation or ESL (English as a Second Language) students that may require some unique or supplemental materials to be covered compared to students may be familiar with American university libraries/research.

Learning Activities

The authors are sharing a collection of lesson plans and learning objects created specifically to address research fears and anxieties among first-year students. The activities listed below were used to prompt and inspire curiosity and inquiry-based exploration of a topic and can be found in this linked toolbox and/or in the references for this chapter (Elliott & Movlai, 2022).

Activity: Digital Escape Room Orientation

The purpose of this activity is to simulate an in-person tour of Healey Library at UMass Boston. Users are introduced to each floor of the library with highlighted information about library services.

Learning Outcomes:

- Students will be aware of various library services.

- Students will familiarize themselves with the different floors of the library.

Delivery: Remote

Summary: The library built a module into the campus’s orientation program that allowed individuals interested in the library to use a digital escape room to “travel” through the 11 floors of the library. The escape room is viewable in our toolbox. All questions are presented as low-stakes interactions, allowing users to answer questions as many times as they like before continuing. The escape room highlighted here was built within Google forms and includes a post-activity survey for users to share their experience.

Activity: Introduction Trivia/Questions

The purpose of this tool is to prompt students to reflect on their own experience with library services in a low-stakes environment.

Learning Outcomes: Learning outcomes can vary depending on the questions used and the goal of the instructor. For the purpose of this chapter, we focused on the following outcomes.

- Students will anonymously identify their concerns or confusion when executing specific research tasks.

- Students will learn about specific library services and tools that help with establishing basic knowledge about a subject.

- Students will learn about what resources they can use to find relevant scholarly and popular sources.

- Students will practice keyword generation in a group setting.

Delivery: In-Person, remote, and hybrid

Summary: This activity is highly customizable and can be easily duplicated and focused on any subject or topic. A mix of both broad and focused questions will inspire students to both reflect on their own information-seeking habits and learn about specific tools and databases that contain the sources they need. You can view examples in our toolbox.

The authors used introductory activities like this as a learning tool. For example, when students respond to “Are all library sources peer-reviewed, scholarly sources?” the class transitions to a larger discussion about why both scholarly and popular sources are available in the library and the benefits of using both in academic research. Open-ended questions about specific subjects are great introductory exercises in curiosity-driven exploration. This is a great opportunity to encourage students to utilize basic internet searches and following links that inspire their curiosity on a topic about which they may know very little.

Activity: Breaking Through Research Dead-Ends

The purpose of this activity is to help students individually, or in a group, determine how to push past a research dead-end. When a search is resulting in no helpful or relevant sources (or way too many), what is the next step?

Learning Outcomes:

- Students will identify additional keywords from articles and database-presented subject terms.

- Students will reevaluate their failed search based on what the problem was (relevance, too many results, not enough) and available sources through the library’s discovery tool.

- Students will execute a new search using newly collected search terms.

Delivery: In-Person, remote, and hybrid

Summary: This activity can be executed a few different ways. Through collaboration with the instructor, a librarian can challenge the class to search for a specific topic together. The librarian can complete the searches and follow steps provided by the students on a projected screen, searching for a topic as a class and experimenting with search terms to explore different results’ pages, particularly when there are no or very few helpful sources on-screen. This also works well as a small group activity, where each group has a worksheet they complete while the librarian and instructor circulate to provide guidance as necessary. Another effective use of this activity is during one-on-one support with a student, either in-class or during a consultation. During this exercise, practice active listening with the student and take notes as they speak.

Methods

To get a better snapshot of the effectiveness of these curiosity-driven lessons and ascertain which information-seeking skills first-year students most struggle with, the authors developed a short, four-question survey. Since the survey is sent out to UMass Boston students, and the anonymized results will be published, the authors went through their institution’s IRB approval process. The data collected from this survey helped librarians clearly determine if departmental lesson plans and activities address student anxieties.

The survey itself is very simple and direct: three multiple choice questions, with an opportunity for respondents to select all that apply, and a final open-text question, all through the SLIDO platform. Librarians read this statement to students to ensure they were informed and comfortable before answering: “Your part in this research is confidential, anonymous, and voluntary. That is, the information gathered for this project will not be published or presented in a way that would allow anyone to identify you. Information gathered for this project will be password protected and only the research team will have access to the data.” After each library session, the librarian downloaded the raw data into a rolling Excel sheet, and entered responses into a Google form, from which the bar charts in the results section are pulled. The survey questions are available in our toolbox.

The fourth question of our survey asked students to reflect on how the library session increased their comfort level in identifying and finding information on their own. We coded responses by reviewing the data, developing the following six themes, and then having each author attach the appropriate theme number(s) to each response. We then reviewed the data as a group to make sure we reached agreement in the few instances where our individual coding differed. We only excluded one entry, “power points,” as we felt it didn’t fit into any of the themes, and didn’t provide enough information to be useful.

Our Themes

- Feelings: comments that note a change in feelings, such as “less worried,” “reassured,” and “less overwhelmed.” We also included general positive or negative feelings like “all good” or “you did great.” within this theme. We notably only received positive feeling statements for both.

- Research strategy: comments that noted the use of Boolean operators, or other search strategies introduced in the session

- Places to search: specific databases and research tools addressed by the student

- Assignment: comments that clearly connect how library resources and search methods can be applied to the successful completion of their assignment(s)

- Contact: comments that specifically address contacting a librarian, finding support, or using chat services

- Citations: Specific comments relating to APA or MLA citation creation or generators

Survey Results

The survey was launched September 2022 to late October and was presented to a total of 413 students in 100-level courses across various disciplines. We had a total of 264 responses, a 63.95% response rate.

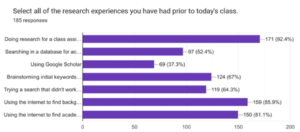

Pre-Session Survey Prior Experience:

Pre- and Post-Survey Research Experience Comparison

At the start of class, we asked students via pre-session Slido survey “What (if any) aspects of research do you find most challenging? [select all that apply]” At the end of class, we asked students via post-session Slido survey “What aspect(s) of today’s lesson did you find most helpful? [select all that apply]” The table below compares the responses.

Coded Raw Data from Open Text:

In our only open-text question, students were asked “In what ways do you feel more comfortable finding and identifying helpful library resources after today’s session?” We received a total of 55 responses with percentages recorded cross all six themes below:

- Feelings: 14/55; 25.5%

- Research: 21/55; 38.2%

- Places to Search: 39/55; 71%

- Assignment: 8/55; 14.6%

- Contact: 7/55; 12.7%

- Citations: 4/55; 7.3%

What We Learned

In comparing the pre- and post-data using the table above, we can see that many of the aspects of the research process students found challenging were also the areas they found helpful, which is one thing we hoped to see. For example, the top three aspects they found most challenging were: finding useful articles, narrowing down a topic, and being able to tell if an article will be useful. Over 50% of participants found each of these aspects useful in the post-session survey. It is of note, however, that the two most useful aspects of the library sessions were knowing where to find articles and using library resources. Anecdotally, we believe that students typically overestimate their skills in these two areas the most. Although they know some places to find articles and have used library resources before, we commonly hear that they are surprised by all of the options presented in a class session. It would be interesting to explore the discrepancy between students not ranking these two categories as challenging in the pre-session, but still finding them the most useful in the post session in future research.

In addition, we received a total of 55 open-text responses, which gave students an opportunity to share their feedback and experiences in an unprompted manner. Overall, students’ responses highlighted increased confidence in utilizing new search strategies (38.2%) and knowing where to look for research (71%). This included the use of Boolean operators, finding and using database provided subject-terms, and purposeful use of our Library’s discovery tool and entry-level databases.

One-fourth of the comments also indicated an increase in positive feelings, with the use of terms like “comfort,” “confident,” and “less overwhelmed” when using library resources on their own. As written about in our literature review, we believe that reducing academic (and library) anxiety is the best path toward increasing curiosity and creativity in first year college students. In-class, curiosity-driven activities were designed specifically to address course-related research assignments that carried significant weight on their final grades, and 14.6% of comments reiterated how the IL sessions would specifically support them in completing this requirement. In addition to the 55.8% of students who found learning how to contact the library to be helpful, 12.7% reiterated their appreciation in knowing that they were able to contact library staff in various, accessible ways, such as telephone, 24/7 chat, Zoom, and email. These open text responses were also very helpful in helping us realize possible options to include in a future post-session survey. For example, we didn’t have citations or assignment help as options, but both were highlighted in the open-text responses.

These findings are very gratifying to us, as most information literacy activities were built around library resources, specifically. All the in-class activities placed heavy emphasis on practicing search strategies and while working through the process of generating keywords from a general research prompt. Not only is this a critical skill in most academic pursuits, it also is a skill in which curiosity is essential. More specifically, it requires multiple ways to think about and phrase a single topic, and having some of those ways fail, another inevitable aspect of approaching research with curiosity.

In addition to these successes, there are clear indications that one-shot instruction in first-year courses cannot address all student anxieties or instructor concerns. In comparing the pre-and post-surveys, we noticed that only ~52-57% of students found our instruction on “finding useful articles,” “being able to tell if an article is helpful,” and “narrowing down a topic” helpful. While students had an opportunity to evaluate sources and draft key terms in class around an example topic guided by the librarians, not all students had the focus or time in class to work on their own topics. This was due to various interferences, like getting clarification on research expectations from the course instructor, lacking a research-topic all-together, in-class socialization, and other variables. To grasp the extent that the variable of not knowing or understanding their research assignment had on the effectiveness of the class assignment, students were asked if “understanding what’s expected of their research assignment” was a challenge, and 53.5% of respondents indicated that was. This struggle is particularly concerning and could potentially alleviate a portion of student research anxiety, and allow for a more curious approach, if students had an opportunity to better understand instructor expectations before the IL session.

Conclusion & Recommendations

As indicated in the literature review, one-shot instruction can only be so effective in impacting student research, information-seeking habits, and research anxiety. These sessions are often only one hour out of the entire time a student spends attending classes, more if they have more than one class that has a library instruction component. Despite this short percentage of time, such sessions can still impact a student’s university and research experience. Therefore, spending time researching how to make them as helpful as possible is worthwhile. For students facing research concepts that cause them anxiety, they need practice and a safe space to follow their curiosity in taking broad topics, breaking them down into searchable concepts, and navigating the abundance of resources available through the library and wider internet beyond.

The authors are aware that this study was conducted over a short period of time, with a relatively small sample size of 264 students in 100-level, introductory classes. However, small surveys like this can serve as an effective tool when conversing with faculty, highlighting students’ self-reported concerns, and collaboratively planning on solutions to address these struggles. We plan on sharing our final survey results with our partner instructors in the hopes that this will lead to more embedded librarian interactions, such as follow-up IL sessions or required librarian consultations, to further enforce strategies introduced in class. We also hope that the inclusion of the survey question regarding the research assignment can help stimulate discussions with instructors. This can help determine the best time of the semester to have a library instruction session and help to increase the frequency of sessions that occur after students have received their research assignment and have had ample time to understand the assignment and choose a topic. In the meantime, librarians are faced with the challenge of asking themselves how we can further inspire curiosity in the research process within and beyond the classroom. Broadly speaking, academic librarians are already trying to create other pathways to engaging with student research with self-driven online modules, research workshops, social media campaigns, and other activities.

References

Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL). (2015). ACRL framework for information literacy for higher education. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Arch, X. & Gilman, I. (2019). First principles: Designing services for first-generation students. College & Research Libraries, 80(7), 996-1012.

Baida, G. (2016). Question formulation: A teachable art. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 23(2), 210-216.

Beghetto, R. (2021). My Favorite Failure: Using Digital Technology to Facilitate Creative Learning and Reconceptualize Failure. TechTrends, 65(4), 606–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00607-7

Carlile, H. (2007). The implications of library anxiety for academic reference services: A review of the literature. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 38(2), 129-147.

Clark, M. (2017). Imposed-inquiry information-seeking self-efficacy and performance of college students: A review of the literature. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(5), 417-422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.05.001

Cooperstein, & Kocevar-Weidinger, E. (2004). Beyond active learning: a constructivist approach to learning. Reference Services Review, 32(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320410537658

Elliott, C. & Movlai, L. (2022). Curiosity learning activities. Google Drive. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1xQTZASvdbnPLucbV2MGrjBBfz3gZ6y4I?usp=share_link

Fister, B. (2022). Principled uncertainty: Why learning to ask good questions matters more than finding answers. Project Information Literacy (PIL) Provocation Series, 2(1), Project Information Literacy Research Institute. https://projectinfolit.org/pubs/provocation-series/essays/principled-uncertainty.html

Fraser, K.-L., & Bartlett, J. C. (2018). Fear at First Sight: Library Anxiety, Race, and Nova Scotia. Partnership, 13(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v13i2.4366

Henriksen, Mishra, P., Creely, E., & Henderson, M. (2021). The Role of Creative Risk Taking and Productive Failure in Education and Technology Futures. TechTrends, 65(4), 602–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00622-8

Hodge, M. (2022). First-generation students and the first-year transition: State of the literature and implications for library researchers. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48(4), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102554

Jiao, Q. & Onwuegbuzie, A. (1997). Antecedents of library anxiety. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 67(4), 372-389.

Kocevar-Weidinger, Cox, E., Lenker, M., Pashkova-Balkenhol, T., & Kinman, V. (2019). On their own terms: First-year student interviews about everyday life research can help librarians flip the deficit script. Reference Services Review, 47(2), 169–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-02-2019-0007

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6)m 1121-1134.

Lemire, S., et al. (2021). Similarly different: Finding the nuances in first year students’ library perceptions. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(4), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102352

Scharf, D., & Dera J. (2021). Question formulation for information literacy: Theory and practice. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(4), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102365

Taylor, R. (1962). The process of asking questions. American Documentation, 13(4), 391-396.

Teagarden, Commer, C., Cooke, A., & Mando, J. (2018). Intellectual Risk in the Writing Classroom: Navigating Tensions in Educational Values and Classroom Practice. Composition Studies, 46(2), 116–238.

Van Der Meij, H. (1994). Student questioning: A componential analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 6(2), 137-161.

Wallin, S., & Diller, K. R. (2022). The scholar’s journey; Transforming the maze into the labyrinth. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102561